Last week I set a goal of not screaming or singing off-key as I entered the chilly waters of my local lake. To add some pressure to meet this goal, I set up my camera so it would record any vocalizations. There might be a wee bit of audible whimpering, but nothing to match the geese and ducks. Enjoy this 3 minute video!

Stages of a Winter Wild Swim

Munn Lake looks so alluring before and after a winter swim It’s real allure during a swim is difficult to define. (Photo my M.M Ruth)

My friend and I had planned a swim on Saturday but it took until Tuesday to finally get in the water. The air was 42 degrees F, the water 46. This does not add up to 100, which is the number someone recommended as a guide to “swimmable” water in “tolerable” air, but we had done 88 before and so proceeded. Someone asked me recently why I swim in really cold water. I will try to explain.

There are three parts to the swim: the before, the during, and the after.

The “before” includes picking a day and time with my friend; dreading the swim (four days’ worth for this particular swim); getting into my bathing suit, fleece, wool socks, wool hat, and dry robe; dreading the swim some more; making hot tea; driving to the lake; standing at the edge of the lake waiting for my brain and body to get in sync and to decide that at this moment right now…now…now (oh, one more photo)…that at this moment now the “before” stage is over.

Self portrait of author while author’s hippie-hatted brain struggles to convince author to stay out of the 46-degree water. Shortly after photo was taken, author told brain to “get over it.” (Photo by M.M. Ruth)

Then the “during” begins with accompanying my bathing suit and wool hat into the water, slowly, up to my waist. My friend is similarly clad and nearby, but she moves more peacefully and steadily. We dip our hands in, splash water on our arms, rub our cold wet hands on our faces, look at the lake and clouds and trees. We talk to ourselves and to each other. We say things like, “Okaaaay!” “Here we go!” “We can do this!” And we do. We just drop so that the water rushes over our shoulders. I flip onto my back and kick and paddle my hands like egg-beaters and try to not scream and sing an operatic off-key note but usually fail. That I am in this very cold lake is bizarre. That I am not crying or weeping or miserable is astonishing. That I am smiling and laughing with my friend is a wild and wonderful gift.

Yes, I am very cold.

Despite my constant thrashing, my hands tingle to the point of discomfort. Is this pain? I am not sure. It’s a feeling. But it’s a sign that if I get out much further in the lake or stay in much longer, my hands—and then arms and legs—will not work well enough to get me back to shore. Keep in mind we are about 30 feet from shore but in water over our heads. We stay in maybe ten minutes then breast stroke toward shore. My friend hands me her wool hat, she dives underwater, and emerges with an even bigger smile. I am not there yet, but soon. I am still seeking and hoping to destroy my idiopathic resistance to putting my head under water.

The “after” of the swim begins when our feet touch the bottom of the lake—about ten feet from the shore—and we lunge for our dry robes, exchange wet suit for dry fleece pants and sweater, and then wrap our hands around a cup of hot tea. We talk. We warm up. We admire the colors and textures of the water, the reflections of the clouds, the harmony of water and sky and trees.

As we begin to feel a bit of post-swim euphoria (endorphins? relief? gratitude?), we slowly head to our cars where one of us will undoubtedly say, “That was perfect. We should swim again soon.” We are vague about when. Here in the “after,” I am not quite ready to start another “before”. I think of a stanza in Wallace Steven’s poem, Thirteen Ways of Looking at Blackbird:

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

At the lake, we do not have to choose. We enjoy both the inflection and innuendo, the whistling and the silence, the water and the air, the during and the after.

The “after” is a really wonderful time and is in no way sponsored by dryrobe, though they do make the before and after quite pleasant, even toasty. (Photo by M.M. Ruth)

Walden Pond is a...Lake

Thoreau’s Walden Pond beckons wild swimmers from near and far. Swimming here is like swimming in a shrine. (Photo M.D. Ruth)

One of the most delightful and serendipitous of my summer’s wild swims of 2019 was Walden Pond just outside the town of Concord, Massachusetts. The Walden Pond made famous by Henry David Thoreau’s book Walden, or Life in the Woods. Now that it’s November and my local lakes in the Pacific Northwest are nearly unswimmable without a wetsuit, it’s the perfect time to reflect back on my wild swim in the mild waters of Walden Pond.

Since first reading Walden in high school, I have always imagined Walden Pond as a pond—a smallish, shallowish roundish body of water. When I first visited Walden Pond when I was in college, I do not recall being struck by the pond’s lake-ish look. I was there to cross-country ski on the trails above the pond, which was completely covered in deep snow.

When my older brother recommended a swim in Walden Pond while I was rambling around New England in September. I thought he was joking. Who would want to swim in a scummy-though-historically-important pond? My brother was not joking and my husband and I set off for the premier destination for a wild swimmer, English major, nature writer, and tiny-house coveter.

Most people who come to Walden Pond do not come to swim. They come to see the pond, to see the cabin where Thoreau lived between 1845 and 1847 in a cabin he built by hand. An estimated 600,000 people visit this site every year to pay homage to this writer and philosopher and to imagine what life was like in the mid 19th-century. Walden Pond and 462 acres of surrounding woods are now protected as a Massachusetts State Reservation (state park) and also a National Historic Landmark. The original cabin the 30-year-old Thoreau built by hand on land owned by his friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson no longer exists but a fine replica has been built for visitors to step into and step back in time.

Despite what our poor memory and imagination want to tell us, Thoreau’s one-room cabin was not in the wilderness. Nor was it remote. Nor was Thoreau a hermit during his two-year stint living here. Thoreau went often to the town of Concord (one-and-a-half miles away) and was visited by friends and family regularly. He lived simply and intentionally at Walden Pond for two years (1845-1847). (Photo by M.M. Ruth)

From Thoreau’s cabin, a paved path leads across a busy road and down to the lake. Yes, lake.

Lakes and ponds are both are slow-moving bodies of water surrounded on all sides by land. Walden is 61.5 acres big and 103 feet at its deepest. That qualifies as a lake in my book and my book is Ernest Walcott’s Lakes of Washington, published by the Washington Department of Ecology in 1973. A body of water with a surface area of less than one acre is a pond. Walden doesn’t come close to being a pond. But “Walden Lake?” That doesn’t sound right. Thoreau’s tiny cabin and story of his two years of life in the woods belong on a pond.

Thoreau’s original cabin was sited on one of five coves of Walden Pond, a cove likely to have been warmer than the rest of the lake and also weedier, muddier, and at times stagnant. Historians believe he accessed the lake from a gravelly beach nearby 432 feet away. Thoreau enjoyed the views of the pond, watched wildlife, went boating and fishing, drew his drinking water, and bathed in Walden Pond. “I got up early and bathed in the pond; that was a religious exercise, and one of the best things which I did.” I am not sure if “bathing” meant taking a bath or taking a recreational swim for Thoreau. As a back-country camper, I think they may have been one in the same.

Thoreau devotes two chapters in Walden to Walden Pond. He waxes most poetically about the remarkable clarity and depth of the water. “The water is so transparent,” he wrote, “that the bottom can easily be discerned at the depth of twenty-five or thirty-feet.” And the color!

The water was palette of blues and greens and ochres that Thoreau marveled at: “Lying between the earth and the heavens, it partakes of the color of both. Viewed from a hilltop it reflects the colors of the sky; but near at hand it is of a yellowish tint net to the shore…then a light green, which gradually deepens to a uniform dark green in the body of the pond.” He discerned a “matchless and indescribable light blue…” (which he goes on to describe). Wild swimmers dream of such water!

I walked slowly, almost ceremonially down the path from the cabin for my first real view of Walden Pond. The colors were just as Thoreau had described.

Walden Pond is full of surprises, including its clarity, range of cool colors, and seeming lack of change since Thoreau’s day. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

Not wanting to rush my Walden Wild Swim, my husband and I sat on the beautiful stone wall above the main beach and just took in the scene—a handful of open-water swimmers steadily stroking their way down the to far end of the pond and back, a few kids playing on the wide beach, small groups of walkers, and some late-season sunbathers. We then ambled along the 1.7 mile “pond path” above the lake, stopping at side trails that lead down the steep hills to small pocket beaches. These small beaches as well as two large beaches are not sandy, but stoney, giving the lakeshore a naturally paved look. Thoreau puzzled over all this stone and suggests in Walden that they originated from broken-down piles of stone created when surrounding land was cleared (for the railroad and other purposes). Thoreau supposes that the name Walden may have originally been called "Walled-in” Pond.

When we reached the far end of the pond at Long Cove, I stripped down to my bathing suit, handed my husband my clothes, shoes, and hat and stepped onto the sandy bottom and into the water. It was pleasantly warm (~80 degrees F).

The length of Walden Pond from Long Cove—a lovely entry point for a Wild Swim. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

And off I went swimming in the water Henry David Thoreau swam in. I was absolutely giddy. I was in water that buoyed not only Thoreau and possibly his friends, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne, but also all the people who visited this pond over the decades since 1847 who knew Thoreau, who read Thoreau, who studied Thoreau, and who thought about his life and legacy while they were swimming. This was a unique swim for me—one that had cultural and historical significance. I cannot think of another pond or lake that holds such an esteemed place in American literature, history, and culture. I was swimming in a shrine.

And when you swim in a shrine, you don’t want to get out. I wanted to swim back and forth all day long as if I were running transects so that I could experience every inch of Walden’s sixty-one acres. Instead, I swam a zig-zagging line into the coves—Ice Fort Cove (a nod to the commercial ice-block harvesting on the pond) and Thoreau’s Cove (site of his original cabin). I popped up often just to look around and the forested hills encircling the pond and to slow my progress toward the end of the swim (had it not just began?) I floated on my stomach and looked through the crystal-clear water to the bottom of the lake. I floated on my back and looked at the cloudless September sky. I think I was bathing as much as swimming this day. Eventually, I swam over to the Red Cross Beach (where swim lessons were taught by the Red Cross) to meet up with my husband who had been walking the path around the lake and taking a few photos from the trail. Here I am (below) swimming in all this gorgeous color and clarity and history.

Thoreau wrote about the wildlife around and in Walden Pond (including the petite Mud Turtle) but failed to mentioned one particular wild resident. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

Just in case you missed it. I’m the long white splash in the upper right. The SNAPPING TURTLE is the massive oval shape in the lower left.

This snapping turtle was basking at the edge of Walden Pond when my photographer-husband spotted it from a clearing on the trail above the pond. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

While the snapper may look tiny in this photo taken well above the water, this fine example of a was about 18 inches long. Snapping turtles aren’t aggressive in the water but I might have lost a finger or two if I had come ashore on this beach where it was basking. I dressed and joined my husband to walk the trail back to the spot where he photographed the snapper. There it was, still basking at the edge of that stunning water. We lingered for a while, oohing and ahhhing and feeling very grateful.

Here’s a very short video of the snapper sliding into the water —to my delight and the delight of a group of 11-year-old boys on the trail with us (and who were carrying a small dead fish they named Wilbur, which they decided to toss into the pond for the snapper).

I hadn’t expected to be swimming with a snapping turtle in Walden Pond. Earlier in the week, in Vermont, I had gotten myself all worked up about encountering during my lake swims there. I knew they were “a factor” for wild swimming on the East Coast, along with water moccasins and lake-side poison ivy—factors we don’t have in the Pacific Northwest. I think perhaps my mind was so focussed on Thoreau, his life of simplicity and stoicism, his contribution to environmental literature, and his near-mythic status among those who know that “back to nature” is the only way to go. Though I know Walden Pond has changed since 1845, I’m grateful that its waters can still hold snapping turtles and swimmers in its liquid embrace

“A lake is the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth’s eye; looking into it which the beholder measure the depth of is own nature.”

If you are anywhere near Concord, Massachusetts, please make time to visit Walden Pond. You can swim, canoe, fish, walk, sunbathe, cross-country ski, snow-shoe, and pay your respects. Here’s a link to a map and information from Massachusetts State Reservation.

Lake Chelan Wild Swim

Mild, not wild. The south end of Lake Chelan in July is a popular destination. The water was warm enough to be popular for swimming (not just dipping ‘n’ screaming) and clear enough to see all the way to the bottom. (Photo by M.M Ruth)

At its south end, Lake Chelan doesn’t say “wild swim” the way other lakes do. At Don Morse Lakeshore Park, it says “recreational lake for summer tourists, locals, and Coppertone.” Which was fine. I’m all for people getting outside enjoying and recreating in nature. This was my first trip to Lake Chelan (pronounced by most as Shuh-lan) and I wanted to experience both this popular municipal beach near the (over)-developed south end of the lake and the remote shores of the north end 55 miles away near the remote village of Stehekin.

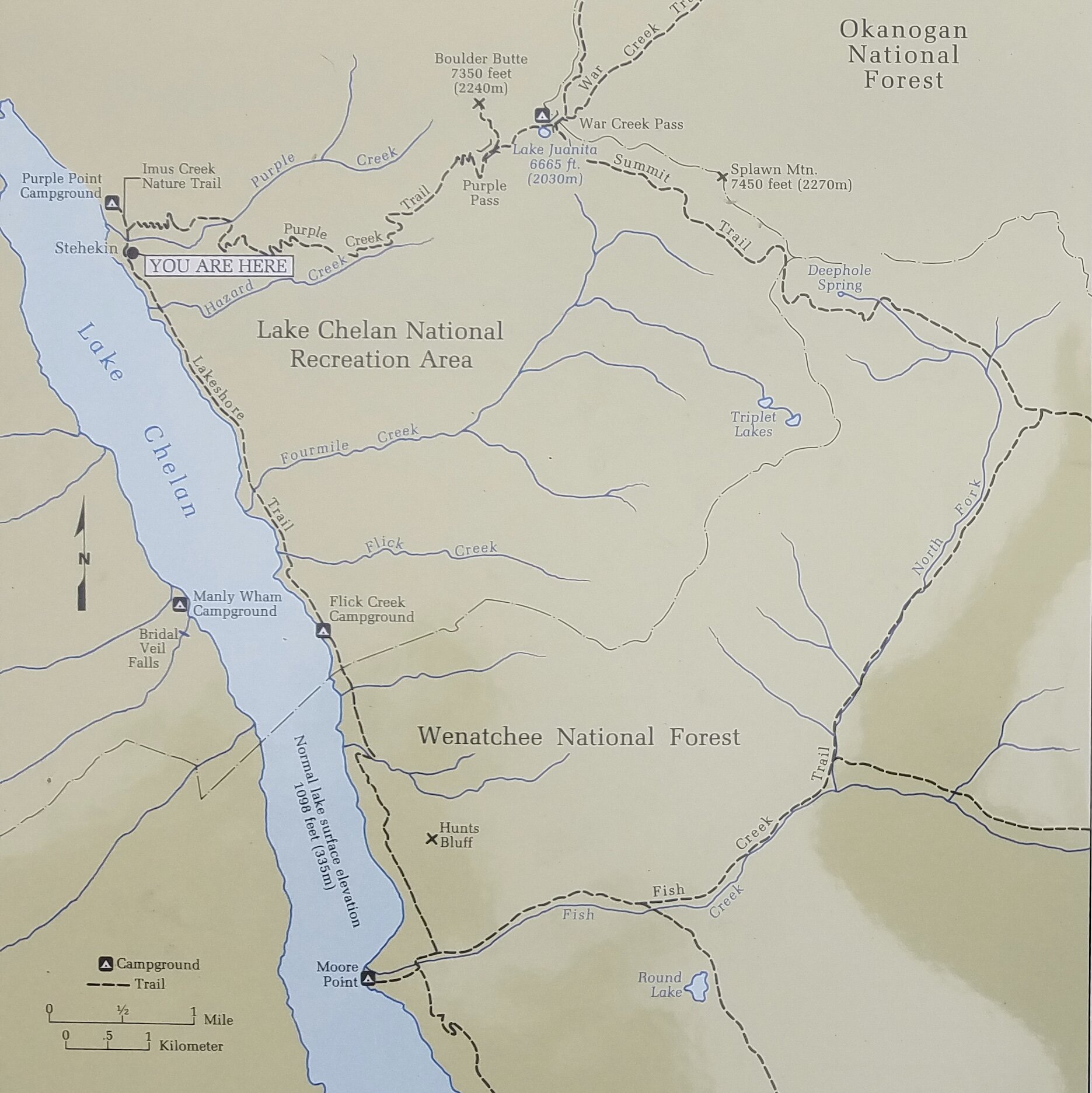

While a swim from the municipal beach was easy (almost a drive-up swim), getting to the remote north of the lake required more planning. Stehekin, like every place along the north half of the lake is accessible only by boat, floatplane, horseback, or by hiking trail.

In the wake of the Pleistocene…a ice-gouged valley and a 1,485-foot-deep lake. (Photo by M. M. Ruth of map on display aboard the Lady of the Lake passenger ferry.

Lake Chelan is 55 miles long, between 1 and 2 miles wide (except at the narrows where it’s just 1/3 mile wide), and snakes its way across three separate Green Trails topographic map sheets (Nos. 82, 11, and 114). This lake is an unfathomable 1,485 feet deep at its deepest . It is the largest naturally-formed lake in Washington, though it cannot be called a natural lake due to the small dam built in 1928 at the south end. Lake Chelan developed in a broad glacial valley during the Pleistocene, about 2.5 million years ago. Everything north of the town of Chelan was buried under the Okanagan lobe of the ice sheet that covered the northern third of Washington. Lake Chelan is steep sided and surrounded by rugged wilderness areas, national forests, national recreation areas, and North Cascades National Park.

Most tourists do not come to Lake Chelan to swim, though there is a “family fun” open-water 1.5-mile Lake Chelan Swim event every Saturday after Labor Day from Manson Bay, eight miles north of the town of Chelan. They come to recreate around Chelan and to take the Lady of the Lake passenger ferry up the lake. Some passengers are bound for Holden Village, a former gold- and copper-mining town and now religious retreat operated by the Lutheran Church. Others deboard at “flag stops” (i.e. flag the captain and he’ll stop/crash the boat along the shore, extend the ramp/gang plank, and send you and your backpack on your merry way into the wilderness).

The Lady of the Lake passenger ferry runs daily trips from Chelan to Stehekin. It’s a grand way to enjoy the scenery, mingle with fellow travelers and residents, and enjoy the ferry captains’ informative narrative. Plan on making unscheduled stops for interesting sights and to drop off and pick up passengers hiking and camping in the wilderness areas surrounding the lake.

The majority of passengers are headed to Stehekin to spend just a few hours exploring the town, the valley, and famous Stehekin Bakery by shuttle bus. Others set off from Stehekin to hike the trails (including the Pacific Crest Trail) in the surrounding wilderness. Overnighters can camp along the lake or stay at the lovely historic North Cascades Lodge. Some will rent kayaks or canoes to explore the lake.

Kayaks rented from the North Cascades Lodge in Stehekin make a great way to explore Lake Chelan but be aware of shifting winds that can make paddling northward a slog. Photo by M.M. Ruth

Stand-Up Paddle Canoeing isn’t the rage yet on Lake Chelan but I recommend it for a pleasant change in perpective of the water and the clouds floating in it. Plus it gives the stearnsman a ridiculous photo op. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

During the two days I stayed at the lodge, I did see two other swimmers (“bathers” might be a better term) but I think I was the only person who swam for pleasure.

“Pleasure” might be a bit of an overstatement. The water at the north end of Lake Chelan at Stehekin was much colder than at the south end. A short hike south on the Lakeshore Trail lead us to Flick Creek campground and a decent-enough access point. And by “us” I mean me. My three companions were not interested in sharing my obsession with wild swimming on this day.

This was one of the briskest swims I took all summer. I’d say it was below 60 degrees—but the clouds and the wind made it seem colder. I guess if meteorologists can talk about “wind-chill factor,” I can talk about “cloud-chop” factor. I swam in 52-degree water in March, but the water was calm and the day was an unseasonably warm and sunny 80 degrees. There is some interesting research on our perception of “cold” water. The air temperature, wind, cloud cover, our mood, our caffeine level, our previous night’s alcohol consumption, and other factors influence not only our perception of the water temperature but also our ability to tolerate it.

Advice: If you are a) solo swimming in a 1,486-foot-deep lake and are b) not wearing a wet suit and c) not accompanied by anyone interested in or willing to get in the water and d) the water is really really cold and choppy and e) it is cloudy and cool…do not stay in long or go far from shore. This swim in Lake Chelan qualified for a-e and so was under ten minutes. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

And shortly before getting on the ferry to return home, I took a swim near the boat docks in front of the North Cascades Lodge. A very easy access point and I had enough time to swim to this mooring log and back. I’m so glad I did so I can keep living up to my motto: Never give up an opportunity for a wild swim.

Yeehaw!

Next Up: Wild Swims on the East Coast, including Thoreau’s Walden Pond (which is a lake).