“Wild swimming” and “open-water swimming” both take place in lakes, ponds, rivers, bays, and oceans, with “cold-water swimming.” Cold-water swimming takes places in natural bodies of water, too, but it is accompanied by xtreme bravado and/or a wetsuit, yelping and/or cold-water acclimatization training, and the risk of both hypothermia and euphoria. At least this is what I thought.

This winter, I have read Lynne Cox’s Swimming to Antarctica(not a metaphorical title). I’ve watched many videos of crazy-happy people dipping into icy lakes in Speedos and wool hats. I stood idly and warmly by while 300 people jumped off a dock and into a lake during the New Year’s Day 2019 Polar Bear Plunge. The water as 40°F that day. No one really “swam,” but they were immersed in that water for at least 30 seconds, which counts for a lot in my book. The Polar Bear Plungers looked ecstatic as they waded back to shore—either because they were glad to be done or because they had quickly reaped the benefits of a dip in cold water: adrenaline rush, exhilaration from increased endorphin levels, and reduced cortisone levels. Or they knew that they would later benefit from increased mental fortitude and clarity, boosted immune system, supercharged metabolism, reduced inflammation, less pain from rheumatism, fibromyalgia, and asthma. What’s not to like about cold-water swimming?

Just some of the 300 swimmers who joined the New Year’s Day 2019 Polar Bear Plunge in the extremely-cold-by-any-standard Long Lake, in Lacey, Washington.

You have to get into cold water.

Really cold water.

But how cold is “cold” water I wondered. “Cold” is very subjective, it turns out. Some people consider water below 70°F “cold.” Others use a standard of 64.4°F to define “cold”—or really “too cold.” This is the temperature at which hypothermia is believed to set in for those people not acclimatized to this temperature and who are suddenly immersed in such chilly water, typically when cast overboard from a boat. Some rare swimmers are acclimatized and habituated to swimming as low as 45°F and do not become hypothermic. Is 45°F “cold” or “too cold” for them?

Cold? Cool? Bracing? Refreshing? Too Cold? It’s up to you to decide.

Because I am planning to write about the natural and human history of several lakes in Washington, I wanted to be prepared for swimming in them when I did my “field work.” I figured I would have to work hard to join the ranks of the elite open-water wild swimmers who frolick in those 45°F waters year-round. I was dreading it. I worried about not only becoming hypothermic but also about just being plain uncomfortable. But wait!

I swim in cold water! I’ve swum in the Tenino Quarry Pool for crying out loud! The water temperature is between 50 and 55°F. In 2018, I swam from April to October in lakes and rivers around western Washington. I doubt any of them were over 65°F. Only once did I feel the water was too cold and that my safety was at risk. I returned to shore as quickly as my sluggish body would let me.

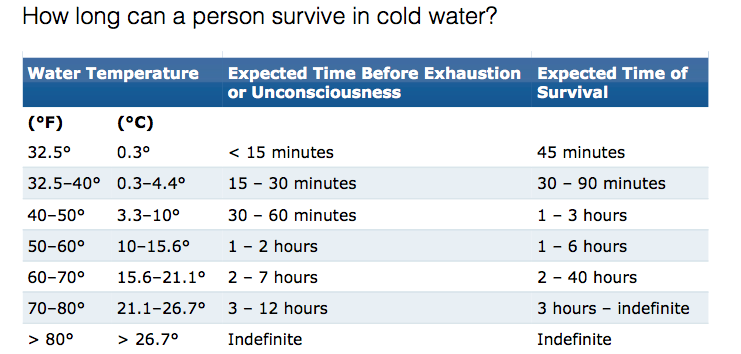

The perception of cold is influenced by many factors: Air temperature as well an individual’s acclimatization and habituation to cold water, physical condition, body size and build, body mass index, attitude, alcohol level, psychological makeup, swimming ability, can affect an individual’s response to the water. The importance of knowing how cold is too cold for yourelates to yoursafety, which is really about and how far and how quickly yourbody temperature drops and you become hypothermic. The temperature of the water and how long you are in the water must both be factored in. A 2-minute dip into 50°F water is one thing, but a 20-minute swim is another.

On the excellent LoneSwimmer blog, I found references to a smart and flexible guide for clarifying “cold.” Using the “Combined 100” method for ranking “cold.” If the combined temperature and water temperature (in Farenheit) is less than 100. For example, when the water temperature is 60°F and the air temperature is less than 40°F, it’s cold. But on a 70°F day, 60 is merely “cool.”

Now that I have convinced myself (sort of) that I am not a wimpy swimmer or an Xtreme cold-water swimmer, I can stop worrying about the semantics and look forward to a long season of wild, open-water swimming in water that may or may not seem to be cold. I have to remember to carry a thermometer to test the water and air temperature before I enter a lake. And I have to pay close attention to how my own watery body responds to being in the water. Relaxing into a nice long swim is a valid response. So is yelping, swearing, and thrashing, and shivering yourself warm.

Meanwhile…while you are learning what “cold” means for you, please look at this helpful chart and info on hypothermia from the Minnesota Sea Grant program’s website:

Write here…