Oh, dear. It's been nearly two months since my last blog posting. What can I say but...wait for it...the clouds got in my way.

The last quarter of 2017 was a busy one ushering my new book, A Sideways Look at Clouds, into the world of readers, skywatchers, cloud lovers, and hunched-over texting addicts. I hope those of you who bought my book (thank you!) are enjoying it, looking up more, and are appreciating the sky and clouds in new ways.

As you may recall, I am posting an excerpt and supplemental content for each chapter of my book you to enjoy. In case you missed them, here are the links to the first three: Prologue /Cloud /Visible

Recall that each chapter of my book covers one term in the definition of a cloud: a visible mass of water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the atmosphere above the earth. This fourth posting covers the chapter on mass--not Pacific Northwest weather guru Cliff Mass, but the mass that is a cloud.

"Though 'mass' has many meanings, the best fit for a cloud comes from the Oxford English Dictionary: 'a dense aggregation of objects having the appearance of a single, continuous body.'

The 'objects' in a cloud are primarily water molecules, billions of them, aggregated into liquid droplets and ice crystals, billions upon billions of them, further aggregated into a single cloud or cloud formation.

The density of this aggregation varies with the type of cloud at atmospheric conditions in which they form. According to one estimated, a typical Cumulus cloud contains about four-thousandths of an ounce of water per cubic yard. This is about a marble's worth of water in a space the side of a loveseat. A typical small Cumulus cloud contains over a million pounds of water--a weight equivalent to roughly one hundred elephants."

from A Sideways Look at Clouds

One of the most fascinating and troublesome problems I encountered understanding "mass" was understanding how so much water could float. Water--the most amazing molecule in the universe--has a trick: as water vapor condenses to liquid water, it releases a tiny bit of energy, known as "latent heat," which gives it the boost it needs to rise above the surrounding cooler air.

My other big problem was visualizing how the mass that is a cloud becomes visible. Part of my problem was imagining the invisible water vapor in our atmosphere and the invisible process of convection that is largely responsible for many of our favorite clouds (cumulus, for instance).

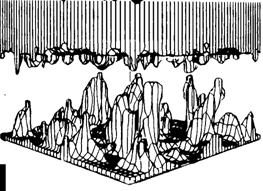

Convection is the process by which warmer air (at the surface of the earth) rises into the cooler air. Many science text books feature diagrams like this one, which relies on arrows to "explain" what is happening.

Convection is the process by which warmer air (at the surface of the earth) rises into the cooler air. Many science text books feature diagrams like this one, which relies on arrows to "explain" what is happening.

Convection is one way air is lifted in the atmosphere. On paper, watercolor artist "lift" clouds using paint and a paper towel. To my delight, I found this out in person while sitting in on a watercolor class at the Olympia Center. After several attempts (chronicled on pages 80-85 in my book), I managed to work the paper towel in the wet paint just so to create some masses that could be recognized as clouds. Sure, there's an elephant trunk in the center cloud and a witch's profile in another, but it sure was fun trying to make paint appear to float.

If you want to try it yourself, here is a very short YouTube video to get you started.

![IMAG2382[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/520a51d0e4b0f89d3274989e/1515097073338-U5HKN7EBW5WFKR73KSS4/IMAG2382%5B1%5D.jpg)